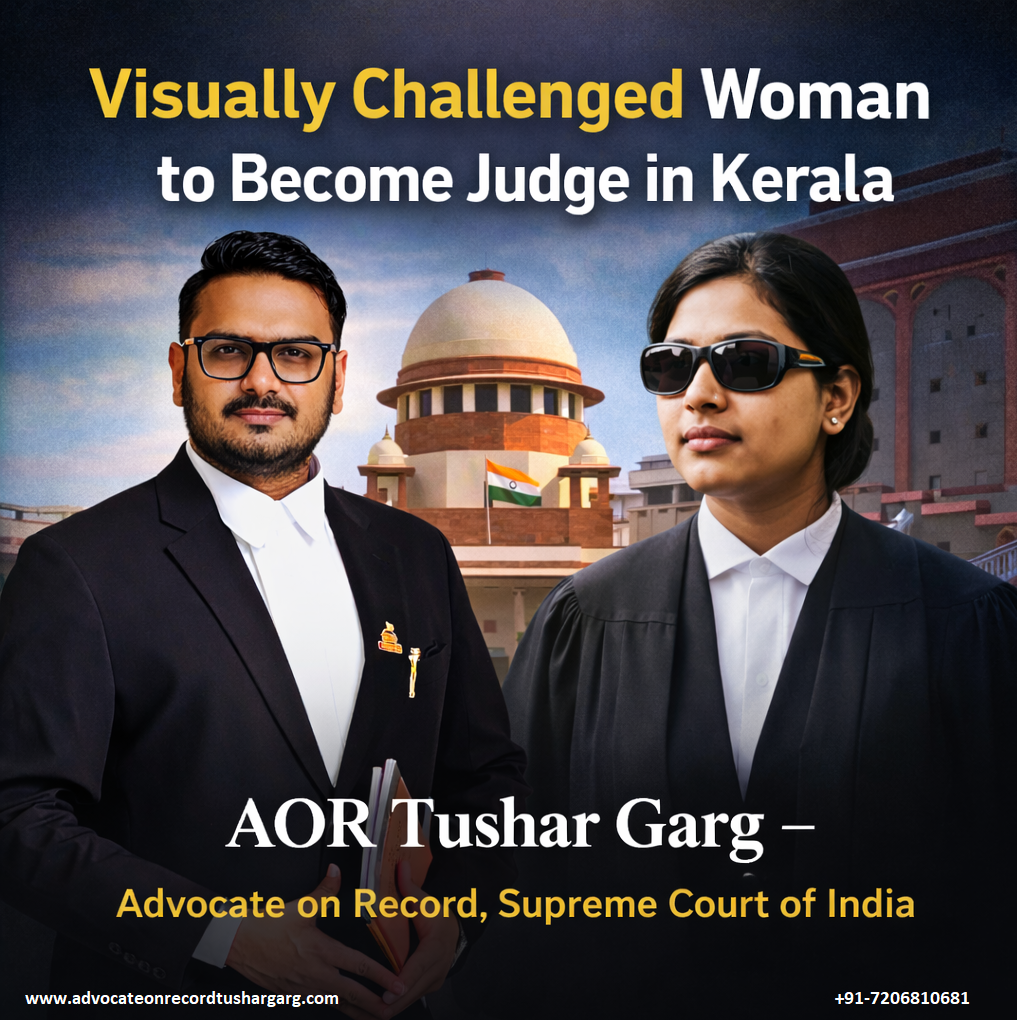

In a First, Visually Challenged Woman to Become Judge in Kerala: A Landmark Moment for Indian Judiciary

India’s judiciary witnessed a truly historic and inspiring moment as a visually challenged woman was appointed as a judge in Kerala, marking a first not only for the state but also for the broader Indian judicial system. This milestone goes far beyond an individual achievement—it stands as a powerful statement on inclusivity, equality, and the evolving mindset of India’s constitutional institutions.

The development has drawn attention from across legal circles, social activists, and constitutional experts, including Supreme Court practitioners such as Advocate-on-Record (AOR) Tushar Garg, who see this as a reaffirmation of the Constitution’s promise of equal opportunity.

Breaking Barriers in a Traditionally Conservative System

For decades, the legal profession—especially the judiciary—has been perceived as conservative when it comes to accessibility for persons with disabilities. While lawyers with disabilities have practiced across courts, entry into judicial services has often remained challenging due to rigid eligibility norms, infrastructural barriers, and outdated assumptions about “fitness” for judicial office.

The appointment of a visually challenged woman as a judge in Kerala decisively challenges these stereotypes. It sends a clear message that disability is not incapacity, and that competence, merit, and integrity—not physical limitations—define judicial ability.

This moment also reflects the gradual shift in India’s institutional thinking, where diversity and inclusion are no longer symbolic ideas but actionable principles.

Constitutional Spirit and Judicial Sensitivity

The Indian Constitution guarantees equality before law under Article 14, prohibits discrimination under Article 15, and mandates equal opportunity in public employment under Article 16. Over the years, the Supreme Court of India has repeatedly emphasized that these provisions must be interpreted in a manner that uplifts marginalized and underrepresented groups.

Legal experts, including AOR Tushar Garg, note that this appointment aligns perfectly with the constitutional vision articulated by the Supreme Court in several landmark judgments advocating reasonable accommodation for persons with disabilities. The judiciary itself becoming more inclusive strengthens its moral authority to enforce equality elsewhere.

The move also resonates with India’s obligations under the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2016, which recognizes the right of persons with benchmark disabilities to participate fully in public life, including holding public office.

Technology as an Enabler, Not a Barrier

One of the key factors enabling this breakthrough is the advancement of assistive technology. Screen readers, digitized court records, speech-to-text tools, and accessible courtroom processes have made it increasingly possible for visually challenged professionals to perform complex legal tasks efficiently.

Courts across India, including the Supreme Court, have accelerated digitization in recent years. E-filing, virtual hearings, and digital case management systems—initially expanded during the pandemic—have inadvertently become powerful tools of inclusion.

According to Supreme Court practitioners, these developments prove that institutional adaptability, not personal limitation, was the real barrier all along.

A Strong Message to Aspiring Women and Persons with Disabilities

This appointment carries immense symbolic value, especially for young women and law students with disabilities who often struggle with self-doubt and systemic discouragement. Seeing someone overcome entrenched barriers to reach a judicial position reinforces belief in merit-based progress.

Women already face structural challenges in the legal profession—from courtroom bias to slower career progression. Adding disability to that equation makes the achievement even more remarkable.

Senior lawyers and AORs practicing before the Supreme Court view this as a reminder that diversity in the judiciary enhances empathy, fairness, and public trust—qualities essential to justice delivery.

Role of the Judiciary in Leading by Example

The judiciary has often played a transformative role in shaping social change—be it gender equality, LGBTQ+ rights, or access to justice. By opening its own doors wider, it strengthens its credibility as the guardian of fundamental rights.

As AOR Tushar Garg and other constitutional lawyers point out, when courts themselves embody inclusivity, their judgments carry deeper legitimacy. It assures citizens that justice is not just pronounced but practiced.

This appointment may also influence future judicial service rules across states, encouraging review of outdated eligibility conditions that unintentionally exclude capable candidates.

Challenges Ahead, But a Strong Start

While the appointment is a landmark, experts caution that true inclusion requires continuous effort. Court infrastructure must remain accessible, staff must be sensitized, and procedural flexibility must be institutionalized—not granted as exceptions.

However, the first step has been taken, and it is a powerful one.

Conclusion

The appointment of Kerala’s first visually challenged woman judge is more than a personal triumph—it is a constitutional milestone. It reflects India’s slow but steady movement toward a justice system that truly represents its people in all their diversity.

For the legal community, including Supreme Court practitioners like AOR Tushar Garg, this moment reaffirms faith in the judiciary’s capacity to evolve with time, technology, and constitutional values.

As India continues its journey toward inclusive governance, this historic appointment stands as a reminder that justice is strongest when it includes everyone.